Fungi are everywhere—they grow in the soil, in petri dishes, and if we’re not careful, on the fruit in the back of the fridge. But did you know it can grow inside plants too? Yes, really! Of course, there are fungal pathogens, which can parasitize a plant, sometimes to the point of death, but much more often, there are fungi living inside of plants in complete harmony! In fact, it’s thought that most, if not all plants host at least one fungus within its tissue, whether it’s a century-old tree or an annual wildflower with the lifespan of a couple months.

These funguses that exist hidden within plants are known as endophytic fungi, or simply “endophytes” for their lifestyle inside (endo-) plants (-phyte). The more we learn about them, the more scientists are beginning to consider the occurrence of endophytes not as some unique phenomenon, but the norm in plants, while the parasitic fungi we’re so used to seeing (of course, their damage is much more visible than the silent work of endophytes) is the exception. Some even suggest certain fungal pathogens begin as benevolent endophytes, before turning to parasitism as a result of some imbalance in the system.

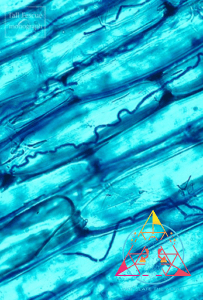

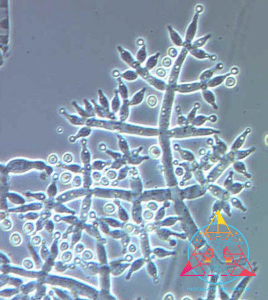

But what does the life of an endophyte look like? Though we can’t quite see them with the naked eye, thanks to their micrometers-wide mycelium that delicately navigates between plant cells, they aren’t necessarily small. Some might just stay within a certain tissue, like a leaf, stem or root, but there are also “systemic” endophytes that can be found just about everywhere in the plant. If we were to somehow see them, these systemic endophytes might look like the nervous system does in humans: head-to-foot (or should I say leaf-to-root) coverage by a nearly invisible network. Once these fungi have been established, they get right to work forming a mutualistic relationship with their host plant. While a plant can provide these fungal associates with food produced by photosynthesis, the fungal associate can take up a number of tasks inside the plant. Non-systemic fungi pitch in wherever they are, whether that’s in the roots facilitating nutrient uptake or in the stem, producing alkaloids to aid the plant’s immune defense. On the other hand, systemic endophytes are capable of many things, including acting as a highway for distributing nutrients, increasing a plant’s drought tolerance, and in at least one case, allowing plants to inhabit areas with toxic levels of petrochemical waste!

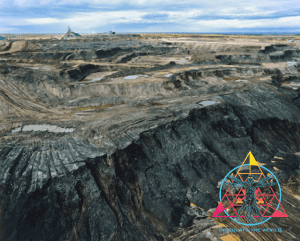

You heard that right! An endophyte has been identified in Alberta, Canada that allows plants to grow on the sandy, oil-covered refuse left behind by mining in the area. Extracted from a dandelion growing in this wasteland, the scientists identified the fungus as a specific strain of the rather common species Trichoderma harzianum, likely starting from spores that landed on the plant. Though it can live in soil, this species thrives once inside the tissue of plants. It just so happens that this specific strain is capable of subsisting on a diet of oil-based chemicals, something that very few known organisms can do.

Lucky for us, this fungus is able to share that incredible superpower with the plants it inhabits! In fact, there’s evidence to suggest that the fungi can utilize the plant’s own materials to break down the petrochemicals, all thanks to a set of enzymes known as peroxidases. Among their other uses, peroxidases have the ability to degrade these hard-to-get-rid-of pollutants. While plants trying to survive on the oily sands without the fungus released some peroxidase, those inoculated with this strain of T. harzianum released over twice as much, a clear advantage when a plant’s trying to make its soil livable.

The end result? With any luck, this sandy, inhospitable environment might once again return to fertile soil, and, maybe someday, that soil could support a thriving forest. Applied elsewhere, T. harzianum might present a more cost-effective, natural way to reclaim polluted soil. All thanks to this miraculous fungus that’s found a way to clean up the messes we made! To quote a movie that needs no introduction, “Life, uh, finds a way.”

Endophytic fungus Epichloë coenophiala weaving its mycelium through tall fescue grass

Trichoderma harzianum

Athabasca oil sands, Alberta, Canada

Works Cited

Kogel, Karl-Heinz, et al. “Endophyte or Parasite – What Decides?” Current Opinion in Plant Biology, vol. 9, no. 4, 2006, pp. 358–63. Crossref, doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.001.

Repas, Timothy S., et al. “Growing Plants on Oily, Nutrient-Poor Soil Using a Native Symbiotic Fungus.” PLOS ONE, edited by Robert Bradley, vol. 12, no. 10, 2017, p. e0186704. Crossref, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186704.

Rodriguez, R. J., et al. “Fungal Endophytes: Diversity and Functional Roles.” New Phytologist, vol. 182, no. 2, 2009, pp. 314–30. Crossref, doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02773.x.

Sánchez Márquez, Salud, et al. “Non-Systemic Fungal Endophytes of Grasses.” Fungal Ecology, vol. 5, no. 3, 2012, pp. 289–97. Crossref, doi:10.1016/j.funeco.2010.12.001.

Shekoohiyan, Sakine, et al. “The Peroxidase-Mediated Biodegradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons in a H2O2-Induced SBR Using in-Situ Production of Peroxidase: Biodegradation Experiments and Bacterial Identification.” Journal of Hazardous Materials, vol. 313, 2016, pp. 170–78. Crossref, doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.03.081.

Related Articles

What Are Rust Colored Mushroom Spores?

Rust spores are cubensis mushroom spores which have turned red, orange, or reddish-brown due to a genetic mutation. When you think of Psilocybe cubensis, you’d typically expect a dark brown or purple spore print, but this is not always the case. Rust mushroom strains...

How to Grow Chestnut Mushrooms

Learn how to grow chestnut mushrooms indoors from scratch in 7 simple steps, from making substrate & grain spawn to ideal fruiting conditions.

The Amanita Muscaria Christmas Legend

The Amanita muscaria Christmas connection may be as old as Santa Claus himself. Learn more about the psychedelic influence on Christmas culture.