Maria Sabina is often remembered as one of the most influential figures in the psychedelic world, renowned for her role as a poet, and shaman, and as the woman who introduced magic mushrooms to Gordon Wasson, and thus, the Western world.

Maria Sabina’s quotes and likeness are widely circulated around psychedelic spaces, which honor her for her impact on psychedelic culture and the history of psilocybin. Her life story and legacy are deeply intertwined with Mazatec culture, as well as the nuanced economic and social impacts of tourism.

Many stories about the Mazatec people are unfairly told from the perspective of Gordon Wasson, or at least frame Wasson’s introduction to the Mazatec people as “the beginning” of the story. In this article, I aim to explain the events of the 1950’s in their appropriate context and significance without centering Wasson’s narrative. The custom of mushroom ceremonies has been an active practice for the Mazatec people long before the 1950’s. Until recently, topics like the significance of these rituals to the Mazatec themselves was frequently left out of the conversation when discussing Maria Sabina, Mexico’s most famous psychedelic healer.

Psychedelic Ceremonies in Oaxaca Mexico

To understand Sabina’s role in history, it’s helpful to understand a bit more about Mazatec healing rituals and the practice surrounding them.

Mushrooms In Mazatec Cosmology

Anthropologists take particular interest in Mazatec cosmology to understand the function of healing rituals for the Mazatec community. Cosmology describes how the universe, and everything in it, came to be, often structured by religion or myths. The belief systems we take up can even influence how we conceive of even the most basic concepts, meaning that something that feels completely objective to one group may be highly culturally specific.

The notion of the mushroom itself is one of these topics. Western classifications consider psilocybin mushrooms to be organisms as well as inanimate objects, composed of chemical compounds such as psilocybin, which can influence how your brain works and what your brain makes of its environment.

Conversely, the Mazatec view the mushrooms as living deities — ndi xijtho (“little ones that sprout”). Rather than inert objects to be consumed, or chemicals to alter your mind, mushrooms are understood as active and agentive beings that can lead, show, and heal.

For the Mazatec, the mushroom ritual encompasses every interaction with it, starting with the picking. Only children, believed to possess innocence and purity, are allowed to pick these sacred mushrooms. Rather than being cultivated from spore syringes or other mediums, mushrooms were found in the wild and treated with the utmost care. They were not commodities to be bought and sold but priceless spiritual entities.

Mushroom Rituals

Mazatec community members turn to healers whenever they are sick or undergoing hardship. The specific type of healing depends on the situation, but those who administer mushroom ceremonies are often called curanderos/as, or sabios/as, or chijnes. In English, these terms are often approximated as “shamans.” Mazatec shamans hold esoteric knowledge that allows them to mediate between different realms, and this role is a huge responsibility.

One healing ritual, called a velada, uses Psilocybe caerulescens and psilocybe cubensis mushrooms to access this spiritual wisdom. These ceremonies are conducted in groups and require special knowledge about timing, preparation, and intention to reach the perceptual reality necessary for healing. A velada is not merely a recreational trip, but a days-long introspective and therapeutic process.

Who Is Maria Sabina?

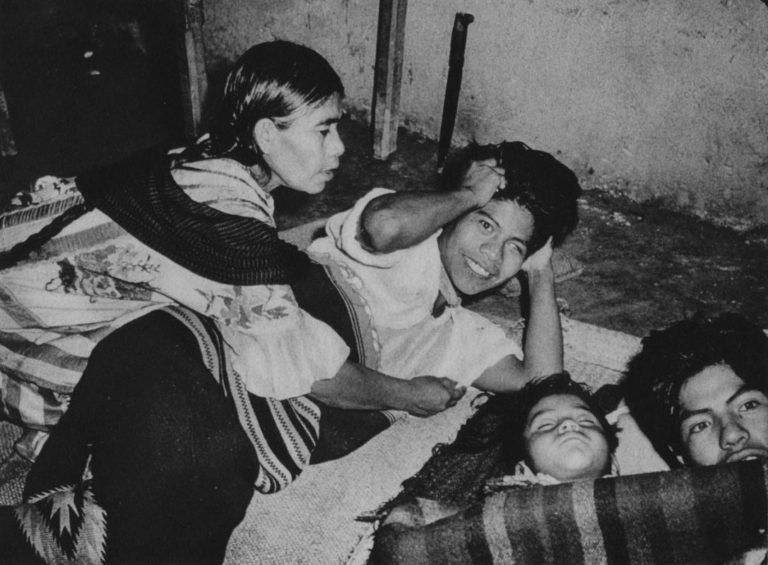

Born in 1894 in Oaxaca, Mexico, Maria Sabina grew up immersed in Mazatec shaman culture. Her grandfather and great-grandfather were curanderos, so she was introduced to these rituals early, even participating in mushroom ceremonies herself as a child.

Sabina became a curandera, or chijne, a healer who administers mushrooms guided by spiritual knowledge. The purpose of these rituals was to open up the mind and initiate contact with God. She was also a poet, composing verses during ceremonies and attributing her poetry directly to the mushrooms themselves.

Though she is singled out in American culture as a martyr figure, she was one of many within a longstanding tradition of Mazatec mushroom healers. Depending on who you ask, a true chijne wouldn’t administer mushroom ceremonies to cultural outsiders, which complicates her role as the first shaman to introduce mushrooms to a group of Westerners..

Maria Sabina and Robert Gordon Wasson

Prior to the 1950’s, Mazatec rituals were sparsely documented by outsiders. Despite the colonization and religious conversion efforts, mushroom ceremonies persisted, often adapted to incorporate Catholic elements.

The Western world didn’t take much interest in these ceremonies until the mid-20th century, particularly through intelligence projects recognizing the strategic potential of altered states of consciousness.

Enter Gordon Wasson, a prominent American investment banker (vice president of J.P. Morgan & Co) and amateur ethnomycologist. With CIA backing under project MKULTRA, Wasson traveled to the Sierra Mazateca to investigate indigenous mushroom use. In the summer of 1955, Wasson, accompanied by photographer Allan Richardson traveled to Huautla de Jiménez, and met Maria Sabina, who administered a mushroom ritual: the first mushroom ritual to be done to a Westerner. Notably, Wasson and Richardson were not ill; they participated purely out of curiosity, which marked a sharp departure from traditional Mazatec practice.

In 1957, Wasson published an article in Life Magazine titled ‘Seeking the Magic Mushroom,’ detailing his experience, from his arrival in the village, to consuming the mushrooms, and the taxonomy of different species of psychedelic mushrooms with detailed photographs. Though he omitted Sabina’s name, he violated many aspects of her privacy, including photographs of her as well as other identifiable information in the article, which ultimately led to her being recognized.

The Aftermath of ‘Seeking the Magic Mushroom’

Wasson’s article triggered a wave of Western interest in psilocybin, from clinical research to a surge in psychedelic tourism. Prior to this boom in interest around psychedelics, coffee was the main economic output and cash crop for Huatla, but this article opened Pandora’s box, transforming the region into a spiritual destination for Western counterculture—sometimes dubbed a “Mexican Tibet.”

Wasson arranged for contacts to gather and sell him mushrooms from there in bulk. He also sent mushroom spores abroad to begin the process of synthesizing psilocybin, which was later used in clinical trials.

Soon, tourists began arriving in Huautla in search of a mystical, mind-altering experience, in one of the most well-known examples of what is now called psychotropic tourism. Hippies, as well as famous artists and countercultural figures like John Lennon made their pilgrimages to Huatla for psychedelic rituals often led by Sabina, in a pilgrimage sometimes called the “beatnik invasion.”

The influx of tourism disrupted the lives and routines of Huautla residents. While the money it brought in could help offset economic instability, especially for a farming village struggling with coffee production, many locals blamed Sabina for the disruption and the spiritual changes that followed. For some, she had become a scapegoat for the broader consequences of global exposure, including the broader spiritual shift in how mushrooms were treated cosmologically and spiritually.

Understanding Mazatec Rituals in their historical context

Amid the new tourist economy emerging in Oaxaca, residents had to adapt to foreign visitors and navigate how their religious rituals were perceived. Greater recognition and global interactions with the Mazatec mushroom ritual caused changes, but this was part of a broader historical pattern that has been unfolding for a lot longer than since the 1950s.

Outside interest in Mazatec mushroom ceremonies carries the risk of misunderstanding and misrepresenting the rituals, or Mazatec culture as a whole. Outsiders often portrayed Mazatec culture as static and “untouched” by modernity. This misconception can also lead to exoticising and inaccurate emphasis on experiencing the customs of a group that is completely ‘untouched’ by modernity and frozen in time.

In reality, Mazatec culture, like all cultures, has always been dynamic, and adapting to the global forces influencing it. Notably, Sabina herself and many other shamans, identified as Catholic while continuing to practice their rituals. This blending of belief systems is common in colonized spaces, where Indigenous traditions adapt to religions imposed during colonization, holding multiple belief systems to be true at once. To call these practices “inauthentic” undermines the legitimacy of these rituals and fails to recognize that all cultures and rituals change over time,

The quest for an “authentic” experience often led tourists to exoticize and stereotype Mazatec rituals, distorting their meaning. Rituals were sometimes commercialized and altered to meet outsiders’ expectations, undermining the deeply spiritual context they were rooted in.

The impact of psychedelic tourism on Oaxaca Mexico

Understanding Mazatec mushroom rituals as part of a broader history of adaptation and cultural change helps contextualize nuanced economic and social impacts of tourism. Mazatec culture has never been isolated or static, but the new visibility of Mazatec culture opened up avenues for appropriation and misrepresentation that scholars and practitioners argue changes the meaning of the ritual itself. The advent of a tourism industry interacts with Mazatec culture in irreversible ways, through both commercialization and notions of ‘authenticity.’ Unfortunately, Sabina was also blamed for these impacts, and for ‘exposing’ a ritual that was once private.

One of the most glaring impacts is the valuation of mushrooms in the first place. Traditionally, mushrooms were not traditionally bought or sold, and were instead thought of as priceless and as part of a religious ritual that wasn’t tied to exchange. Tourists introduced a demand for transactions, and a market emerged. Some practitioners see this commercialization as a spiritual rupture in how the mushrooms are used and understood.

The lack of continuity comes not just from commercialization, but also from fundamental changes in the performance of the ritual itself through the search of “authenticity’. When tourists visit in search of an ‘authentic’ experience, they come to expect a specific performance that is outside of their typical experience, while also conforming to a mystical image constructed by pop culture. In a way, the tourists were seeking the ‘authenticity’ of an isolated and ancient ritual, creating simplistic, stereotyping narratives around the indigenous populations, or profiting from these ideas themselves. As the ritual becomes commercialized, certain aspects of it may be changed or flattened over time to meet consumer’s expectations, often violating existing social conventions around mushrooms.

Maria Sabina’s Legacy today

Sabina was put to shame in her own community for her role in introducing magic mushrooms to foreigners, and faced severe backlash during the later years of her life. She spent those last years in poverty, and later died from malnutrition in 1985. Today, she is celebrated for her contributions to psychedelic spaces and Mexican literary history, often without full acknowledgment of the harms caused to her and her people.

Recognizing her contributions also calls for recognizing the rich traditions she came from and contributed to. In their article on the subject, Florez, López, and Alcántara use the term “biocultural appropriation” to describe the Western use of Mazatec cultural and spiritual assets. Participants in mushroom rituals often fail to acknowledge the unequal power structures that shaped their access to those traditions. This is not to say that outsiders can’t participate in Mazatec culture when invited, but instead that people should reflect critically on cultural exchange and respect indigenous cultural property without prying or commodifying.

We can’t right the wrongs of the past, like the harms that have already been done in the Mazatec community, but we can do a better job of listening from here on out. There are many ways to take mushrooms therapeutically, and cultural outsiders need to critically reflect on the drive to experience an ‘authentic’ Mazatec mushroom ceremony. People should learn from Mazatec people and what they want to share without fetishizing their experience or profiting from their image and the asymmetrical power dynamics shaped by the region’s history. True respect means moving beyond curiosity or aesthetic appreciation and toward a relationship of mutual respect.

By centering Indigenous voices and supporting community-led initiatives, such as Esperanza Mazateca, a non profit initiative build by Inti García Flores to provide support to Mazatecos, we can honor Sabina’s memory and celebrate Mazatec culture without repeating the harms of the past.